Yoshita 1967

Rooted in ancestral craft and carried forward by a collective of women artisans in Kenya, Yoshita 1967 is redefining luxury through meticulous craftsmanship and an uncompromising commitment to ethical labor.

We spoke with Anil Padia about growing up in Nyeri, about the point where he chose instinct over external expectation, and about how working with crochet and film has become a way to honor women, craft and cultural inheritance.

Interview EMILY PETRUCCIONE

Introduction NICOLE GAVRILLES

Images courtesy of YOSHITA 1967

Yoshita 1967 is a Paris Nairobi based label defined by handwork, precision and a commitment to craft. Founded by Anil Padia, the brand brings together memory, lineage and technique to create garments that feel both intimate and expansive. Rooted in the designer’s Kenyan Indian upbringing and shaped by years of working between cultures, Yoshita 1967 treats fashion as an evolving archive, a way of carrying forward stories while reimagining what luxury can look like today.

You grew up in Kenya, where your family migrated over a century ago. Can you paint a picture of that upbringing that laid the foundation for your creativity?

I grew up in Nyeri in central Kenya, where my family had settled after migrating from Gujarat over a century ago. Life at home was steeped in Gujarati customs and traditions, while life outside the house was shaped by Kenya’s environment and culture. That mix, moving between two worlds, shaped how I see things and gave me a sensitivity to difference that continues to inform my work.

Being sent to boarding school at a young age made that pull even stronger. The Christian education I received there often stood in sharp contrast to the traditions of my family, and I struggled with that divide. It was difficult, and at times disorienting, but it also made me attentive to detail and alert to the subtleties of culture and identity, things that later found their way into my work.

You’ve said your mother’s style and a Bollywood film changed your life. Can you take us back to that moment when your love for fashion began?

My earliest sense of style came from my mother and the women in my family. I grew up in an extended household where several generations lived together. As a child I would watch intently as my grandmother, my mother and my aunts prepared themselves. I remember them opening jewellery boxes, laying out silver pieces, carefully choosing the colours of the bangles they would wear. Adornment was not superficial, it carried care, presence and meaning. Those moments of watching the women in my family get ready shaped how I began to understand beauty and dress.

You’ve spoken about carrying a hidden inner feeling from a young age. How did your family’s acceptance influence your identity and creative expression?

My family has always amazed me. They never allowed themselves to get stuck in time, even when everything around them seemed fixed. They grew, adapted and pushed past their limits. For that I am deeply grateful, for their ability to love beyond what they did not always fully understand. And by family I do not just mean the nuclear one as it is described in the West, but the wider circle who all shaped me in different ways.

Even when I could not fully name what I was feeling as a child, especially around being queer and different, I found expression through art, movement and costume. My family did not close the door on that. They gave me the space to explore, even if it was not always easy. That early acceptance became the foundation I return to whenever I question myself or step away from what others expect.

“That mix, moving between two worlds, shaped how I see things and gave me a sensitivity to difference that continues to inform my work.”

You went to Central Saint Martins—what led you there? Were you already designing at that point?

I was sketching long before I called it designing. Clothes and silhouettes, drawn secretly behind schoolbooks. I went to London to do a foundation course at Central Saint Martins partly to test whether fashion was a path I could walk. It was intense, emotionally, culturally and financially overwhelming, and I did not complete it. After that I then came back to Kenya where I did my first internship with a local brand called Kooroo. Each step felt crooked, but each one taught me something technical or emotional that I later used in Yoshita.

You went to Paris to study and worked with high fashion houses. What technical skills or philosophies from those chapters have stayed with you?

Later I moved to Paris to study fashion and spent time with houses like Paco Rabanne, Y Project and Jacquemus. There I learned and explored my draping and pattern making skills, how a garment moves, how finishes matter. Those standards of discipline and craft stay with me always. It helped me develop an acute sense of detail, every hem, every thread, every technique is subject to enormous scrutiny before it is approved. That level of precision is something I now carry into Yoshita.

During Covid, you experienced a turning point, rejecting trends and traditional taste. What was the first thing you did after that shift?

The real turning point came during the pandemic. I stopped paying attention to what I thought the world was saying and tried instead to listen to myself. In my journey from London to Paris I had lost confidence and with it my inner voice. This was the moment I chose to reclaim it. I decided to be bold and walk into fabric stores in Nairobi, picking whatever drew my attention without questioning whether it was chic or cheap, cool or tacky. I just knew I liked it, and that was enough. That voice is what I am still training myself to hear, even if it is not always easy to find beneath the noise.

Was there a specific moment or object that crystallized the idea for the brand?

I first met Catherine during my first internship in Kenya. When lockdown came, we began working together again. At first it was simply about experimenting, making small pieces, testing ideas, exploring crochet and what might be possible. But in that process something larger began to take shape.

The beginning of Yoshita 1967 came from the meeting point of two needs: on my side, a need for creative expression, and on Catherine’s side, the chance to continue and grow her craft. It was not about one of us giving to the other, but about what we built together. That balance became the foundation of Yoshita.

One of the first pieces we made was a baby blue polo shirt in crochet, embroidered with small glass mirrors. At the time it felt like an experiment, but it became a turning point, since the technique of crocheting with mirrors has now become a staple in my work.

The name Yoshita honors your aunt and your grandfather’s business. How are you weaving your family legacy into the brand?

The name Yoshita honours both my late aunt, who was born in 1967, and my grandfather’s business, Yoshita Industries. In Sanskrit, the word yoshita means woman. For me, carrying that name is a way of remembering my aunt while also grounding the brand in a lineage of women. My aunt lived with disability and mental health challenges in a society that not only stayed silent about such things, but often failed to understand and rejected them. Family and societal taboo are central themes in my work. Through Yoshita I try to bring to the surface the whispers of unspoken truths, giving voice to stories that were never fully heard, including my own.

Local craftsmanship played a central role in the beginnings of Yoshita 1967. Why was this important to you?

From the beginning, craftsmanship was at the heart of Yoshita 1967. Crochet and other forms of handwork have long existed within the community, but they were rarely given the visibility or respect they deserved. I wanted to centre those overlooked skills and the women who hold them, not as decoration or hobby, but as the foundation of the work. Every piece was made by hand, using cotton threads, crochet and detailed embellishment, and treated with the same level of precision and technique as any fashion house in Paris. What mattered to me was that the women behind the work were recognised, valued, and that the craft itself was seen as equal to any standard of luxury.

“Every choice, whether it is thread, embellishment or labour, has to respect heritage, the environment and the people behind the work. That is what gives me clarity and direction.”

Temple Road, your debut collection at SS25 Paris Fashion Week, was the result of a long incubation period. How did time shape the final pieces, and what did that launch mean to you?

My debut collection in Paris was the result of two years of preparation. It meant training with artisans, refining techniques and holding the work to the same standards of precision I had learned in Paris. Too often, craft from our region is seen as peripheral, decorative or less rigorous. For me it was the opposite. Every seam and every detail had to be exact. Showing the collection in Paris was not about proving ourselves but about affirming that this level of excellence can emerge from our context. The launch was a dream come true, but also one I had shied away from for far too long.

You debuted the collection alongside a film of the same name. What inspired this cinematic pairing?

The film is an extension of the universe I am building with Yoshita. Clothes can hold memory, but film allows me to show what cannot be seen on the surface, sound, movement, atmosphere. It ties together the larger themes that form the poetic and deeper layers of my work. The result has a dreamlike quality, evoking a place and a ceremony that at once exists and does not, where things that belong and things that do not are merged, yet held in one space. That space is the Yoshita universe.

Silver bells echo throughout the collection. What do they signify?

Silver bells are at the heart of Yoshita. They are my obsession, because they hold so many layers at once: culture, dance, heritage, family memory. I even scanned my mother’s anklets with their silver bells, and they became the starting point of creation. Through them, sound becomes craft. The bells are a universe within themselves, an invocation I return to again and again.

You lead by intuition rather than trend. What does trusting that process feel like?

Trusting intuition has meant stepping away from outside validation. It meant feeling unsafe sometimes, doing things that feel raw or imperfect by conventional metrics. I had doubts: “Am I too ornate? Is this too slow?” But over time, letting what feels true guide me has brought the work that resonates most deeply. Listening to oneself is no easy feat. We lose our voice so often, and much of the journey is about trying to unravel and return to that voice again and again. It is uncomfortable at times, but it is also where the core of Yoshita lives.

“My vision is to create a women’s community centre where the artisans we collaborate with can access holistic care, financial literacy, education and other essential resources including health and food support.”

What is the process like working with your artisans? How long does a piece typically take?

Our process is very much technique driven. We begin with exploring techniques, then move into embellishment, then colour, and finally shape. All our pieces are 100% handlade, and each one can take weeks to complete. Crochet is extremely labour intensive. Sometimes you wait weeks for a sample only to realise it does not work, and then you wait again for the next attempt. The work is slow, very slow, but that patience and rigour are part of the integrity of Yoshita.

You’ve spoken about reclaiming lineage through craftsmanship and sustainable design. How do these principles guide your processes?

Sustainability and lineage are not separate concerns for me, they are the way decisions are made. Reclaiming lineage means centering techniques that were always there but often overlooked, and carrying them forward with value and visibility. We only work with materials and processes where there is the right capacity, fair compensation and cultural meaning. I am not interested in fast cycles or trends. Every choice, whether it is thread, embellishment or labour, has to respect heritage, the environment and the people behind the work. That is what gives me clarity and direction.

Your production unit is made up of 26 women. Who are they?

We work with two groups of women. Our development studio, now six women, is made up of people from the community around us, many of them single mothers we reached through word of mouth. The aim was to create stability and autonomy through craft. We also work with a group of missionary nuns who came from Zimbabwe to Kenya in the 1960s. They are highly skilled and form part of our production line.

Your visual identity is stunning. How do you collaborate with creative partners to bring it to life so intentionally?

I am very precise about the visual identity I want to create, but it is always a collaborative process. So far the identity has drawn strongly from my family’s migrational history, and that universe has been enough to hold the work. I have been fortunate to find creative partners in Nairobi, photographers, directors and producers, who understand this language and have helped bring it to life. Now I feel ready to move on from that foundation and explore more subtle layers. The next collections will open a new chapter in the Yoshita visual world.

You just launched the brand’s website – exciting! What was your vision for its digital presence?

The website is not only about retail, it is about building a universe. I want it to feel like a space of discovery, where people can enter the world of Yoshita through film, archive and stories as much as through the clothes themselves. It should hold the same sense of depth and resonance as the physical work, allowing visitors to see that every piece belongs to a wider context of culture, collaboration and imagination.

How do you envision someone wearing Yoshita pieces in the future?

I imagine Yoshita being worn in daily life and in special moments. I want women to feel beautiful and adorned, and to use the clothes as a way of reconnecting with their sensuality. For me it is about creating pieces that celebrate women, and if my work can play even a small part in helping them feel more connected to themselves, then it has done its work.

Togetherness and community were values you were raised with. How do you hope to carry those forward in the next chapter of the brand?

I hope to grow with the community we have built so far, the women we work with and the creative partners too. My vision is to create a women’s community centre where the artisans we collaborate with can access holistic care, financial literacy, education and other essential resources including health and food support. Yoshita can only grow if the community around it is nourished. We are linked to each other, and no one should be left behind. In the end, Yoshita is a community, and its strength is measured not by what we create alone but by what we hold together.

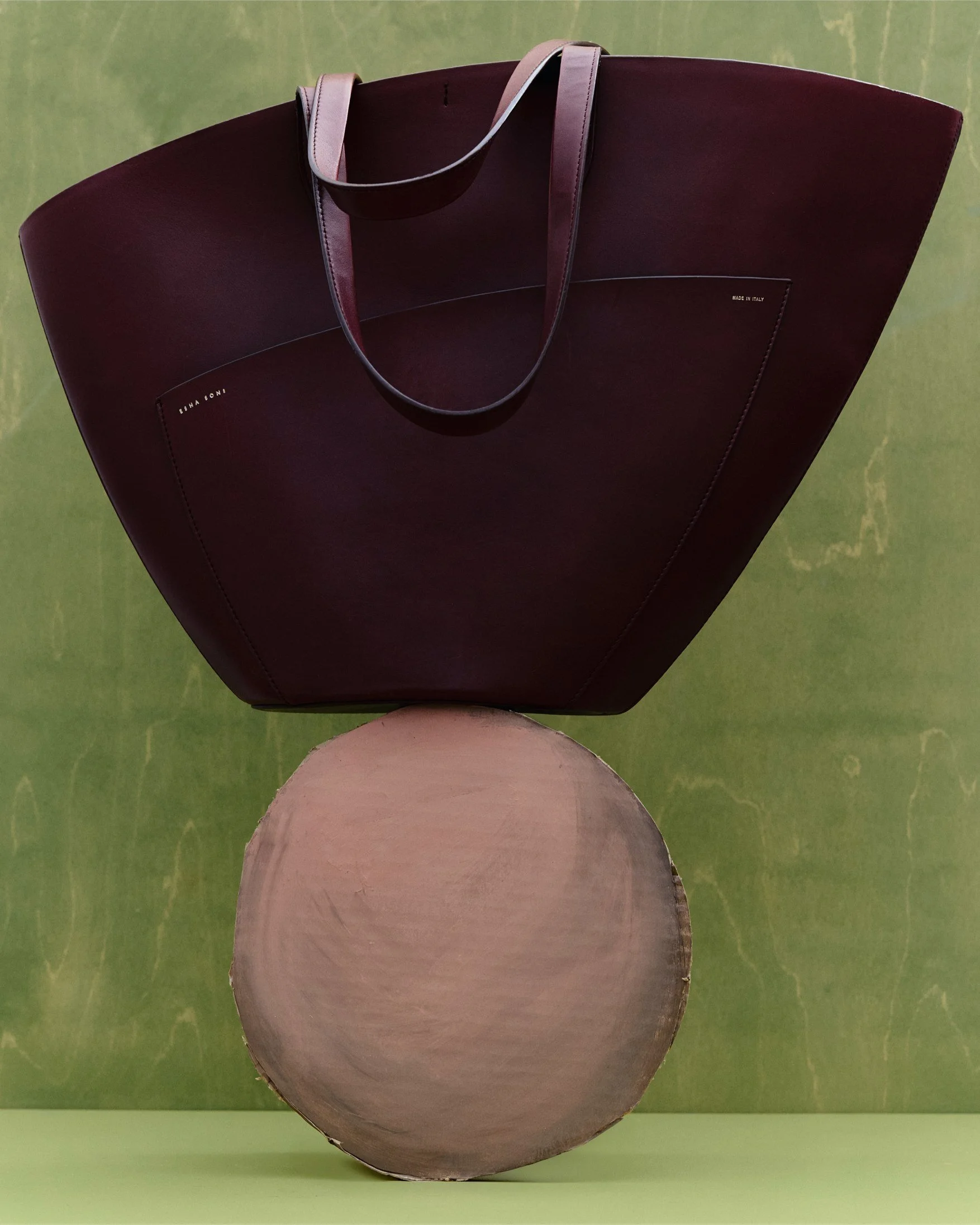

Yoshita 1967 is a Paris Nairobi based brand founded by designer and artist Anil Padia. The brand is defined by a dedication to craftsmanship, a precise design language, and a commitment to creating garments that feel both timeless and modern. For more information, visit yoshita'1967.com

Images courtesy of Yoshita 1967

YOU MIGHT ALSO LIKE

We spoke with founders Clio Dimofski and Olivier Garcé as they discuss the origins of their practice, the role of materials and artisanship, and their approach to creating spaces and objects with quiet strength.